The forgotten

“T” in ESG

The forgotten “T” in ESG

Driven by a perceived link between ESG factors and financial performance, and a desire to promote their own values, the general public and investors are increasingly interested in ESG investments. One aspect of ESG that has, to date, seen less of a focus than it arguably deserves, is tax.

Tax considerations permeate all ESG considerations. Taxation (as a mechanism for wealth redistribution) is inherently socially driven, with measures such as research and development reliefs, charitable exemptions, and the United Kingdom’s (U.K.) diverted profits tax and off-payroll working rules, intended to benefit broader society through incentivizing or discouraging certain behaviors. However, these regimes typically develop organically within their respective spheres rather than being introduced to further an “ESG objective.”

Looking beyond this inherent social element:

Generally speaking, domestic environmental tax legislation is piecemeal and consists of sector or energy-specific measures designed to discourage certain behaviors and draw funds from profitable industries. Notably, the U.K., following a “the polluter pays” policy, has historically imposed significant additional taxes on “bad” energy sources (largely gas, petroleum and solid fuel sources). There are also additional taxes on plastics, the exploitation of aggregate and landfill operations. Although there are enhanced capital allowances for investments in environmental technologies, intended to operate as a green energy tax incentive, these are largely overshadowed by the impact of the U.K.’s blanket energy levies.

Generally speaking, domestic environmental tax legislation is piecemeal and consists of sector or energy-specific measures designed to discourage certain behaviors and draw funds from profitable industries. Notably, the U.K., following a “the polluter pays” policy, has historically imposed significant additional taxes on “bad” energy sources (largely gas, petroleum and solid fuel sources). There are also additional taxes on plastics, the exploitation of aggregate and landfill operations. Although there are enhanced capital allowances for investments in environmental technologies, intended to operate as a green energy tax incentive, these are largely overshadowed by the impact of the U.K.’s blanket energy levies.

Indeed, the recently introduced electric generator levy and energy profits levy, imposing windfall taxes on energy profits, apply to both “good” and “bad” sources of energy, thereby significantly reducing the commercial incentive to invest in green and sustainable energy.

With further uncertainty as to the appropriate tax treatment of transactions involving emissions credits and woodland carbon credits, there is clearly much potential for progress in this area.

The proposed European Union (EU) Carbon Border Tax, the “biggest climate law ever in Europe, and some say the world,” shows promise in driving a concerted global effort to reduce emissions. Although still in its infancy, the tax, if implemented as proposed, would significantly raise the price of importing certain classes of goods with high manufacturing emissions into the EU, with the burden to reduce the tax by showing low manufacturing emissions placed on the exporter. While draconian and far from actual implementation, the tax has the potential to lead the reshaping of global trade in an environmentally beneficial manner.

Indeed, the recently introduced electric generator levy and energy profits levy, imposing windfall taxes on energy profits, apply to both “good” and “bad” sources of energy, thereby significantly reducing the commercial incentive to invest in green and sustainable energy.

With further uncertainty as to the appropriate tax treatment of transactions involving emissions credits and woodland carbon credits, there is clearly much potential for progress in this area.

The proposed European Union (EU) Carbon Border Tax, the “biggest climate law ever in Europe, and some say the world,” shows promise in driving a concerted global effort to reduce emissions. Although still in its infancy, the tax, if implemented as proposed, would significantly raise the price of importing certain classes of goods with high manufacturing emissions into the EU, with the burden to reduce the tax by showing low manufacturing emissions placed on the exporter. While draconian and far from actual implementation, the tax has the potential to lead the reshaping of global trade in an environmentally beneficial manner.

Investors are showing an increasing interest in tax strategy. In addition to financial concerns, whereby companies face penalties and fines for tax evasion or avoidance, there is a developing reputational concern for investors.

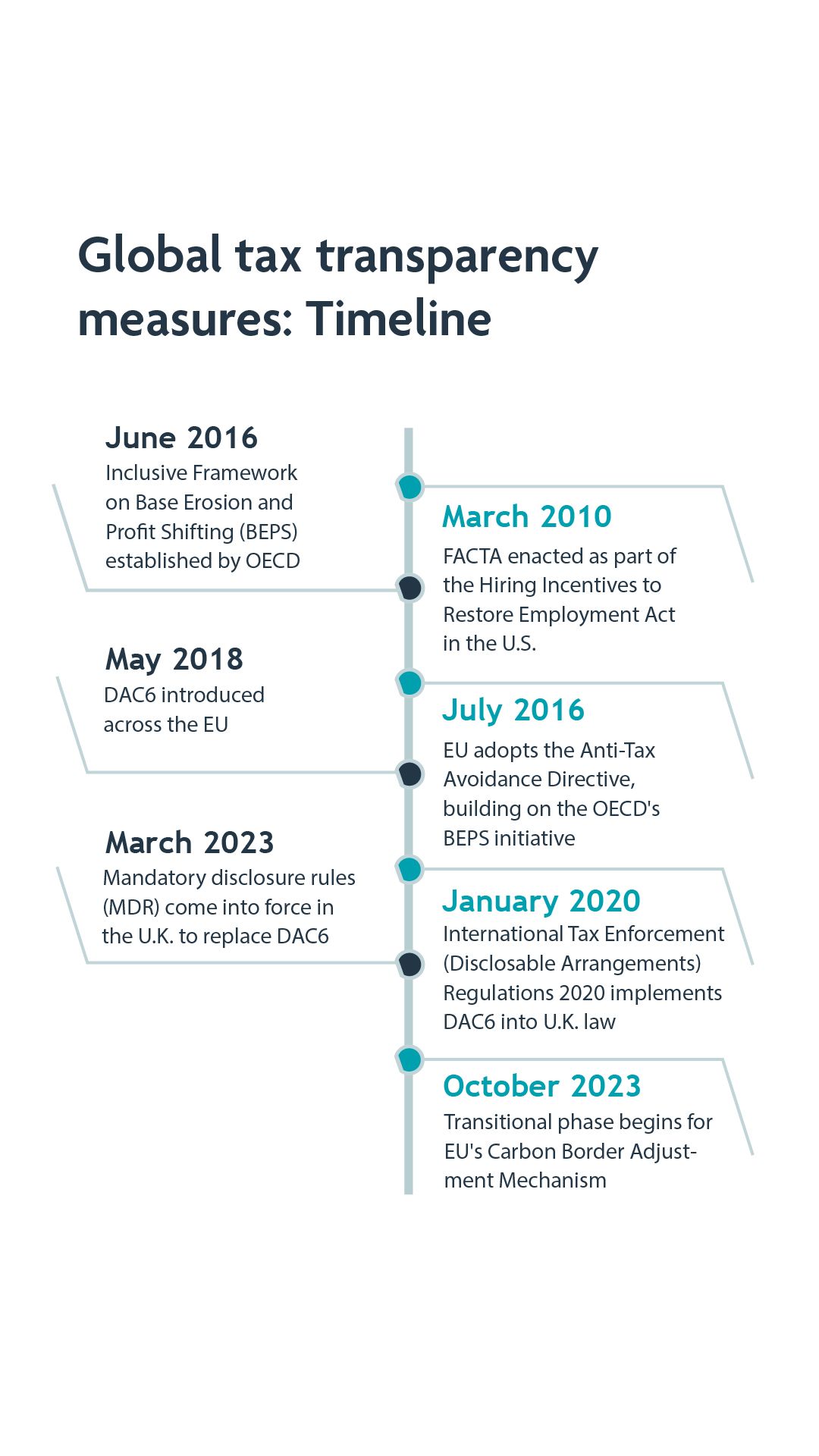

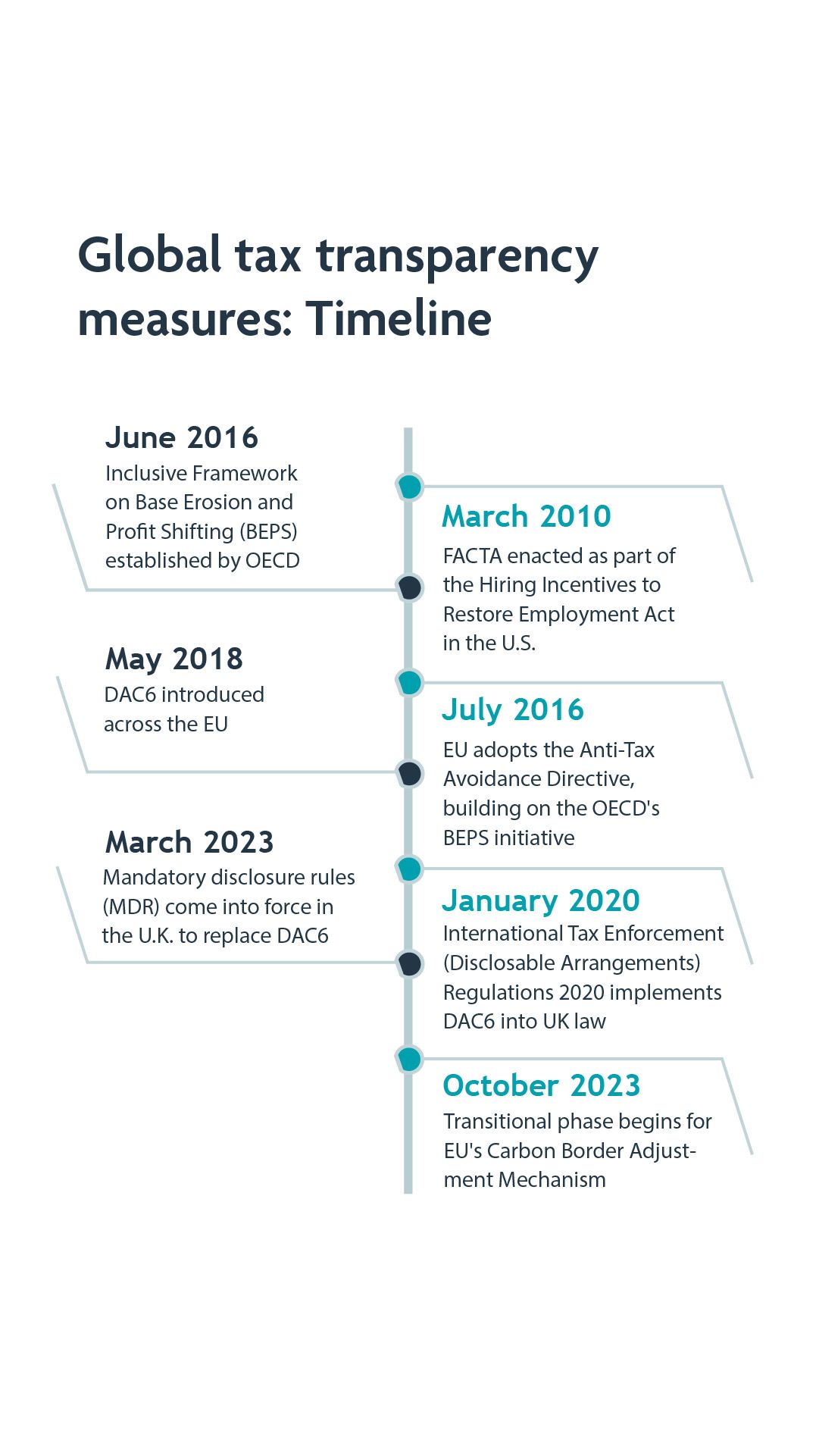

Globally, reporting obligations and transparency measures have been spearheaded by the United States (U.S.) Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Common Reporting Standard, requiring greater tax transparency from companies. In addition, in the U.K., with the introduction of the Code of Practice on Taxation for Banks and (more recently) the mandatory publication of tax strategies for large businesses, larger companies face increasing tax reporting obligations. Obligations in respect of potentially aggressive tax structures have been broadened by implementation of select “DAC6” hallmarks in the U.K. (soon to be replaced by the mandatory disclosure rules).

These reporting obligations have been backed up with substantive legislative change, such as the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directives, sparked (primarily) by the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. This ties in with investors’ increasing concern with the manner in which, through taxation, a business contributes to the international community. To this end, some investors favor investments deemed to be paying tax in “appropriate” jurisdictions. Viewing legislatively mandated standards as insufficient, such investors turn towards a number of voluntary metrics to measure and report on ESG tax performance, including the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) industry-specific standards, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) 207 tax standard and the International Financial Reporting Standards’ (IFRS) proposed Sustainability Disclosure Standards. These metrics can, however, be problematic to the extent they fail to provide a consistent benchmark for performance and reporting standards. Some investors, such as Google, have started relying on internal ESG metrics owing to the inconsistent external approach. The reluctance to use what could be considered “aggressive” tax structuring is therefore only partly driven by legislation – it is also heavily influenced by investor concerns and reputational risk regarding appropriate governance and social contribution.

Investors are showing an increasing interest in tax strategy. In addition to financial concerns, whereby companies face penalties and fines for tax evasion or avoidance, there is a developing reputational concern for investors.

Globally, reporting obligations and transparency measures have been spearheaded by the United States (U.S.) Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Common Reporting Standard, requiring greater tax transparency from companies. In addition, in the U.K., with the introduction of the Code of Practice on Taxation for Banks and (more recently) the mandatory publication of tax strategies for large businesses, larger companies face increasing tax reporting obligations. Obligations in respect of potentially aggressive tax structures have been broadened by implementation of select “DAC6” hallmarks in the U.K. (soon to be replaced by the mandatory disclosure rules).

These reporting obligations have been backed up with substantive legislative change, such as the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directives, sparked (primarily) by the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. This ties in with investors’ increasing concern with the manner in which, through taxation, a business contributes to the international community. To this end, some investors favor investments deemed to be paying tax in “appropriate” jurisdictions. Viewing legislatively mandated standards as insufficient, such investors turn towards a number of voluntary metrics to measure and report on ESG tax performance, including the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) industry-specific standards, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) 207 tax standard and the International Financial Reporting Standards’ (IFRS) proposed Sustainability Disclosure Standards. These metrics can, however, be problematic to the extent they fail to provide a consistent benchmark for performance and reporting standards. Some investors, such as Google, have started relying on internal ESG metrics owing to the inconsistent external approach. The reluctance to use what could be considered “aggressive” tax structuring is therefore only partly driven by legislation – it is also heavily influenced by investor concerns and reputational risk regarding appropriate governance and social contribution.

In the U.S. context, despite political backlash, investors’ enthusiasm for ESG products and business strategies, at least from an environmental perspective, is apparent in the fact that major asset managers have not yet opted out of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative. A handful of asset managers have also taken steps to implement and enforce SASB standards, with State Street having developed its own “R-Factor” score. However, the extent to which tax governance ESG measures are implemented will largely depend on the underlying rational for prioritizing ESG products.

The U.S. approach to ESG is largely premised on the principle of ESG products’ profitability, seeing State Street proclaiming that investment in stocks as a potential solution to climate change is a “matter of value, not values.” However, aggressive tax strategies inherently involve minimizing social contributions. ESG commitment to a tax strategy with greater social contribution, and implicitly a larger tax bill, would necessarily reduce profits. Ultimately, the extent of asset managers’ ESG commitment in both the U.S. and Europe is driven by investor enthusiasm – material nonlegislative commitment to ESG tax strategies would likely form part of a broader ESG commitment and need to be driven by a matter of values, not value. Although European investors seem more focused on ESG values than their U.S. counterparts, it remains to be seen whether such enthusiasm will translate into material differences between U.S. and European tax planning.

In the U.S. context, despite political backlash, investors’ enthusiasm for ESG products and business strategies, at least from an environmental perspective, is apparent in the fact that major asset managers have not yet opted out of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative. A handful of asset managers have also taken steps to implement and enforce SASB standards, with State Street having developed its own “R-Factor” score. However, the extent to which tax governance ESG measures are implemented will largely depend on the underlying rational for prioritizing ESG products.

The U.S. approach to ESG is largely premised on the principle of ESG products’ profitability, seeing State Street proclaiming that investment in stocks as a potential solution to climate change is a “matter of value, not values.” However, aggressive tax strategies inherently involve minimizing social contributions. ESG commitment to a tax strategy with greater social contribution, and implicitly a larger tax bill, would necessarily reduce profits. Ultimately, the extent of asset managers’ ESG commitment in both the U.S. and Europe is driven by investor enthusiasm – material nonlegislative commitment to ESG tax strategies would likely form part of a broader ESG commitment and need to be driven by a matter of values, not value. Although European investors seem more focused on ESG values than their U.S. counterparts, it remains to be seen whether such enthusiasm will translate into material differences between U.S. and European tax planning.

Authors

Serena Lee

Partner

serena.lee@akingump.com

London

T+44 20.7012.9650

F+44 20.7012.9601

v-card